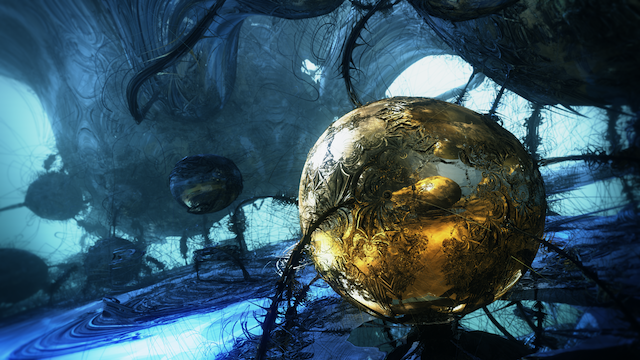

Filmmaker Julius Horsthuis, the frequent explorer of fractalized caverns and endless alien planets, has begun a line of computer-generated experiments that could let us explore our own Interstellar-like multidimensional realities. His impressive series of sweeping fractal vistas, beginning with Geiger’s Nightmare nearly a year ago, has given him a wealth of knowledge about making gorgeous fractals. Now, he has channeled that experience into building Hallway 360VR, the first in a line of 360-degree virtual reality animations.

Even though most of them came out months before Interstellar’s release, many of his animations remind us of a particular scene in the Christopher Nolan epic. “[Nolan’s] films are very visual and create a strong sense of presence,” Horsthuis told The Creators Project. “In Interstellar, I was delighted to see fractals translated into a film—and very well executed too.”

That delight translates equally well into his own fractal creations. Horsthuis has developed a talent for bending the 3D fractal generation software, Mandelbulb3D, to his sprawling visions, adjusting colors, camera angles, and other factors to create his immersive experiences. Now that he’s translating that knack into the burgeoning field of virtual reality, he is currently grappling with many of the same challenges faced by innovators like Nonny de la Peña and Marshmallow Laser Feast. We spoke to Horsthuis about fractal generation, Interstellar, and the challenges of adapting animation to VR.

The Creators Project: How did you decide to begin expressing yourself through these intricate fractal worlds?

Julius Horsthuis: I have been in 3D animation and Visual FX for several years, and have always been fascinated by emergent shapes and patterns. When I first saw a 3D fractal, I was mesmerized. I had been thinking about it for quite some time when I first tried to create something with Mandelbulb3D. Although I knew my way around traditional 3D software, this seemed alien to me. But through a helpful community of enthusiasts sharing parameters—the lifeblood of 3D fractals—I picked it up pretty quick. There’s no need to understand the math behind it at all. Then I started to apply the experience I had with traditional film and animation to the fractal renders: lighting, framing, pacing, editing, etc. The response was just so positive that I found myself continually trying out new things and just learning.

Can you give me a brief explanation of your process?

I fiddle a lot with new parameters, or open up an old set and start changing sliders. Nine out of ten times this results in nothing much, or just crazy unrenderable noise. But every now and then a pattern starts to emerge that looks like something totally awesome. Then I usually save my work, and start trying out to build an animation around it, sometimes working forward in the timeline, sometimes backwards. Also this is when I need to decide the basic color scheme or lighting direction. I then make a preview render, check it for errors and start rendering.

This can take up to a week, but also sometimes a day or two (on a render farm). During rendering, I mostly start playing around with the look and feel in After Effects, color correcting, lens flares, and what not. When the whole thing is rendered, I load it up in Premiere, where I can timestretch, and pick music that suits it. Then I render out in After Effects where it all comes together.

Tell me a little bit more about the kinds of parameters you need to adjust when making fractals.

Parameter files are very small files, that contain the pivotal formulas. In Mandelbulb3D, they are sliders that give you real-time feedback. They have names such as “fold,” “Julia factor,” or “Min R.” Sometimes their effect is quite obvious, (scale, rotate) but other times, especially when mixed with others, their effect is very unpredictable. But because of real-time feedback, it’s somehow comprehensible.

The most interesting and complex fractals usually emerge when mixing various formulas. Mandelbulb3d has 6 slots for formulas, and there’s at least 100 formulas to pick from, and they all have their own sliders. Mixing these is where most of the magic happens. The order and the number of iterations also have effect on the look of the fractal.

What is the biggest challenge when you’re putting together a new project?

Usually the hardest part is to decide on a mood. The color scheme, the speed of the camera flying through, or the music determines a large part of what the experience will be like, and since my influence on the exact shapes themselves is severely limited, it’s all these other factors that set the mood. Even after rendering the whole thing in 3D, I can decide to change the colors to something light, and re-time the animation to something quick, or do the opposite, and create something slow and dark.

Other challenges might be of a more technical nature, such as reducing noise or getting rid of other disturbing artifacts. This is something that you get better at the more you do it. Also, the rendertime vs. quality decision can be a burden on my patience.

How is designing a fractal world for VR different than designing a 2D video?

VR fractals, although I have only made a test animation and am now in the (very long) process of rendering a much biggger 360-degree animation, are completely different. Although the technical process is very similar, all the tricks I know as a filmmaker / animator can be thrown out the window. There’s no camera, so we have to treat it more like an architect would treat his ‘audience’. I have to do more experiments, but I think the traveling camera must be much much slower, since there’s just so much to see when looking around. I haven’t got much experience with this yet, but I’m really looking forward to be doing more of these. Since the experience is just that much more intense there is no need for ‘in your face’ stuff, and very subtle music cues paired with lighting changes can bring profound emotions in these fractal worlds.

How did the need for architecture-like design manifest in your recent test footage?

My test footage is really just that: a test. There are also mistakes in it, but it shows, I think, that we can experience the fractal world like we experience a place. Rather than having a timeline, which states this happens and then this happens, we put the viewer in a place and let them explore it by looking around. Of course, we are still bound to a timeline, because it’s not a real-time render, so we determine the pace, and what happens, but the viewer needs to feel in control of where he/she can look. The emotions may still come from revelation, not by showing something, but by literally putting the viewer into a place.

How do you use to elicit particular emotions in your animations?

The pacing and speed is important because it determines how much the viewer can see from the shapes. When does a particular pattern become boring? I try to use reduce color palettes, to give more attention to the shapes and framing.

I’ve always loved cameras and lighting, so this is where I spend a lot of time. When I worked on film sets, I learned and loved the magic of lighting, of how it can transform a dull looking set (or actor) into something dramatic and fascinating, that I try to apply these same principles to the fractals. It really makes such a difference, when lit and framed cinematographically.

When determining the animation, I also try to use very simple principles as buildup, climax, etc. Sometimes I fail at this, and I think that my work has succeeded best when the pacing works. Lure the viewer in, try to make him curious about the next shape, and then reveal or transform into something unexpected.

You said that there is no need to know the math behind fractals to get started in Mandelbulb3D. Have you since learned more about that math? Do you feel there is any value to be gained artistically from learning it?

The actual math, including complex numbers, is still completely alien to me, but I have gained a feel of their effects, and can predict them up to a certain level—maybe like a surfer, who doesn’t know the very complex physics of fluid dynamics, surface tension and navier-stokes equations, but can predict very accurately what will happen. So, in a way, he ‘knows’ them.

Another example is the 4-dimensional rotation. Some fractals are in fact 4D, projected back into 3 dimensions. When rotated in the fourth, it seems to be morphing, but actually it’s just different bits of the 4-dimensional shape that come into view. The fourth dimension is impossible to imagine, but playing with its rotation makes is somewhat understandable.

Which artists give you insight into designing fractal worlds, particularly for VR?

I love film, and a lot of my inspiration comes from there. Worlds that are created for film inspire me, such as Christopher Nolan’s Inception and Interstellar. These films are very visual and create a strong sense of ‘presence.’ In Interstellar, I was delighted to see fractals translated into a film—and very well executed too.

Another theme in his work is the passage of time, reverse time in Memento, dream time in Inception, relativity in Interstellar, and even though there’s no direct link from this to my work, it’s somewhere in the back of my head all the time. My recent fractal, Nothingess, was mostly based on the feeling of the multi-dimensional scene from Interstellar.

Other examples in Nolan’s work are the nested worlds in Inception—the fact that we have knowledge of the scene in the van, when we are actually in the hotel. This stuff really helps the experience of a fractal, when we’ve seen where it is in relation to something else, even if we don’t perceive it directly.

Another master at this kind of world building was Stanley Kubrick, and other inspiration comes from nature, and I’m very interested in evolutionary biology and cosmology.

What do you think your audience can gain from being able to explore a fractal world in virtual reality?

Fractals tell us something about the way the world works, and this, to me, is just incredible interesting. The idea that something seemingly complex and infinitely detailed can come from very simple beginnings is paradoxical. Either there’s something magic about math that it can do this, or—which I think is more likely—the detail and complexity is just an illusion, enhanced by the fact that our brains with which we perceive this, are made with the same fractal processes.

Visit Julius Horsthuis on Vimeo to view more of his incredible 3D fractal creations.

By Beckett Mufson

Source: Vice.com